The following text is a personal account by German photojournalist Peter Bock-Schroeder (1913-2001), recounting his experiences working for various magazines in the post-war period.

Bock-Schroeder discusses his love for landscape and street photography and how it provided an avenue for him to pursue his career. He also shares his thoughts on what constitutes a photojournalist's landscape and the importance of personal observations and trial and error in photography.

The photo reporters' message

In 1964, the editors of Quick, the groundbreaking German photo news magazine, published the work of a dozen of its leading contributors.

Each of the photo journalists included in the volume, Report Der Reporter, were invited to discuss their art in an accompanying essay.

Among the photographers highlighted was Peter Bock-Schroeder, who vividly chronicled life on the far flung fringes of the post war world in his journeys as a foreign correspondent for Stern and Revue magazines, as well as Quick.

In a letter to the editors of Quick magazine, German photojournalist Peter Bock-Schroeder (1913-2001) described his work in the following words:

The photo journalist’s landscape

Geographical pictorials are the pet hate of every editor in chief of every major illustrated current affairs publication. There is no such thing as a landscape photographer at a magazine.

And that is why for me landscape photography is something like a flight from the pictorial feature I am usually told to do.

But if it has to be landscape, then at least make it "photo journalist’s landscape," as one of the most accomplished magazine makers used to say. He draws a line at your common, garden variety landscape photos, which means not only sunsets, moonrises, fields and forests, but every view one might consider "pretty." And yet it is still the best escape for me from my job.

I suppose I have to take a few steps back to make that more understandable: Where does my fascination for photography come from and how did I become a photo journalist?

What counts is the perception, the eye

The advantage I was born with was probably a good eye, which has enabled me to enjoy an excellent photographic career. A little further down the road, a friend of the family, who believed to have discovered a visual talent in me, took me to one of Berlin's most renowned photo studios, Atelier Binder on Kurfürstendamm, run by Frau von Stengel.

The tuition fee was 150 Reichsmarks a month, and one could consider oneself privileged to be an apprentice in this very well managed studio. That didn't save anyone from having to take the so called taste test, me included. Fortunately I passed.

It perhaps deserves mention that the studio had already shaped colleagues with such great names as Erich Balg, Sonja Georgi, Hubs Flöter, Friedrich Aschenbräuch and Jo Niczky.

Anyway, in the time that followed I was rotated around the various stations, practicing my skills at retouching negatives, then positives, playing the peek-a-boo clown for children's portraits or even going to buy the bread rolls for the boss.

He then recognised that my talent might go further than these responsibilities and advised me to go to a school for photography.

So it was that after a few months at Atelier Binder, I registered for the Bräuhaus school in Berlin, where the well known photographer Erich Balg taught. The little technical know how I have, I owe to him.

For example, one of his school exercises was to take a photo of Brandenburg gate as no one had ever seen it before, using only a very rudimentary camera.

Yes, a new way of seeing something that had already been photographed millions of times. I took my shot of it looking between the legs of the police there, an unusual perspective at the time, and got a good grade.

A Life in Photography

While attending that school I went on a field trip to Holland, where I first discovered my love of landscape photography. I was fascinated by the vastness and cleanliness of the country.

Snow white cloud formations on the blue horizon, children with clogs on their feet, that's how I saw the island of Volendam. It was the first feature I was paid for.

After two years of school my journeyman period began. I went to Sweden, Holland, England and Belgium, big trips in pre war times, and they gave me so much, both for my personal development and for my photography. Travel is the best education for a photographer.

I was able to experiment and shoot however I felt like. I had time, there were no "musts", and earning a living wasn't an issue.

I was married to my camera, and of my entire career, these wander years were the time I enjoyed the most. The photos I took during those years of travel were my best.

Beyond Pretty Pictures

But back to the photo journalist’s landscape. The way I see it, you can find this breed of landscape anywhere. It isn't dependent on any given light or season.

Scruffy roads are as much a part of the landscape as the typical pictures of green islands.

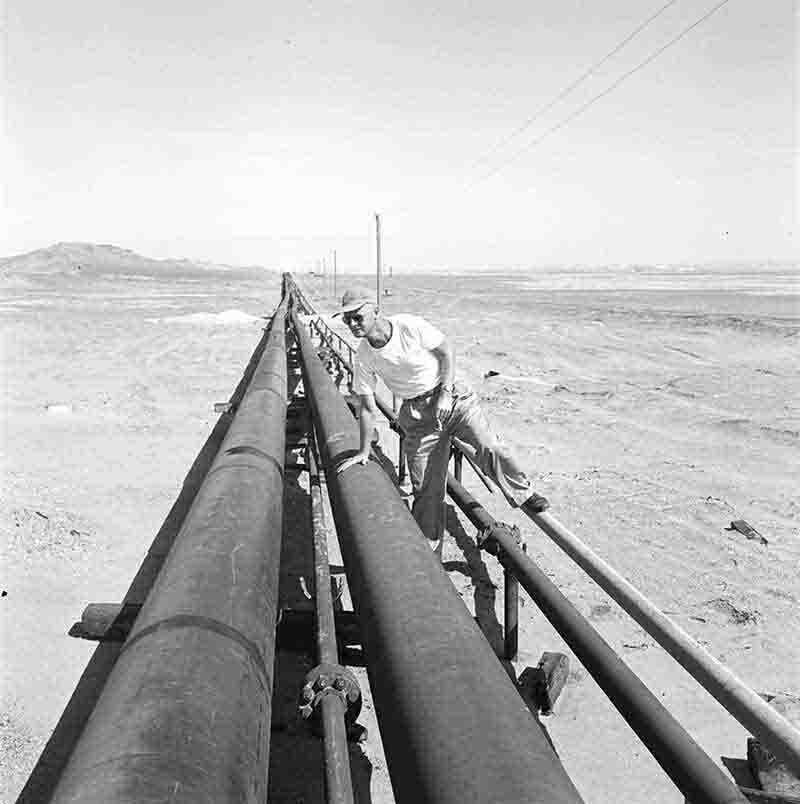

For me, the pipelines in the desert of Talara in the north of Peru are much more symbolic than the admittedly highly picturesque scenes in the oil city Talar.

Of course, on that job I tried to capture the special atmosphere of this hot desert town with its stunningly beautiful creole women and the lazing Indios that contrasted so wonderfully with the feudal American country club with swimming pool.

But nonetheless, those pipelines leading off into eternity still left more of an impression on me.

The importance of experimentation in photography

For Alaska the commission was to shoot an extensive pictorial about the German emigrants there and the willingness of this north-westernmost point of the American continent to defend itself with military means.

A visit to a radar station in Alaska brought considerable difficulties with it. For understandable reasons I was checked over any number of times by various military officials before the permit was issued.

But as appealing as the job seemed, just as disappointing was what the place had to offer from an optical point of view. The actual function of this kind of radar station, known as the Green Eye (or was it blue or red?), is quite impossible to capture with a camera. What to do?

After convincing myself at first hand that the food and accommodations for these hand-picked soldiers were excellent, if not necessarily my taste, I trotted around the near surroundings, always a little worried I might break one of the rules, and in doing so suddenly discovered a certain angle from which to document the contrast between the endless, barren expanse of the tundra and the ultra modern military base.

This photo shows the isolation and bleakness of the landscape in the midst of which the futuristic military defence facility, which itself doesn't deliver much in the way of visual highlights, stands.

The way I see it, this picture epitomises the term "journalist landscape" particularly well. An amateur landscape photographer probably wouldn't think of taking photos of this uninviting scenery, though perhaps a spy might.

From Atelier Binder to the World

The same is true of the photo of Mamai Hill near Stalingrad that became so famous in the war.

Since Stalin gave the order to completely rebuild the city of Stalingrad in 1945 for reasons of prestige, it was difficult to find anything reminiscent of perhaps the greatest tragedy of World War II in the city.

I had expected to find ruins, but despite my best efforts I could only discover buildings in the customary confectionary style.

There was an old observatory presented to the city as a gift from East Germany, in which I saw the original Russian film Stalingrad.

Deeply stirred by this staggering documentary, I took a taxi straight to the tractor factory that had been so bitterly fought over, and then to Mamai Hill, which had attained the tragic fame of having soaked up the blood of thousands of soldiers from both armies.

It is astounding: nothing there reminds you of the huge battle except a tank turret on a stone pedestal and an inscription. For me, that photo is Stalingrad.

Sure, there are much more scenic shots you can take of the Volga, but this is the way it appeared to me, a little grey and eerie, because I knew what a significant role it had played in the winter of 42/43 when it was frozen over.

The impact of unusual perspectives

After returning from the Soviet Union I was often asked what it was really like over there, whether the taxis were old or new, if there were omnibuses and hairdressers, whether there were fashion stores, photo studios, friendly policemen, popsicles and all that, and I tried to answer all these questions to the best of my ability.

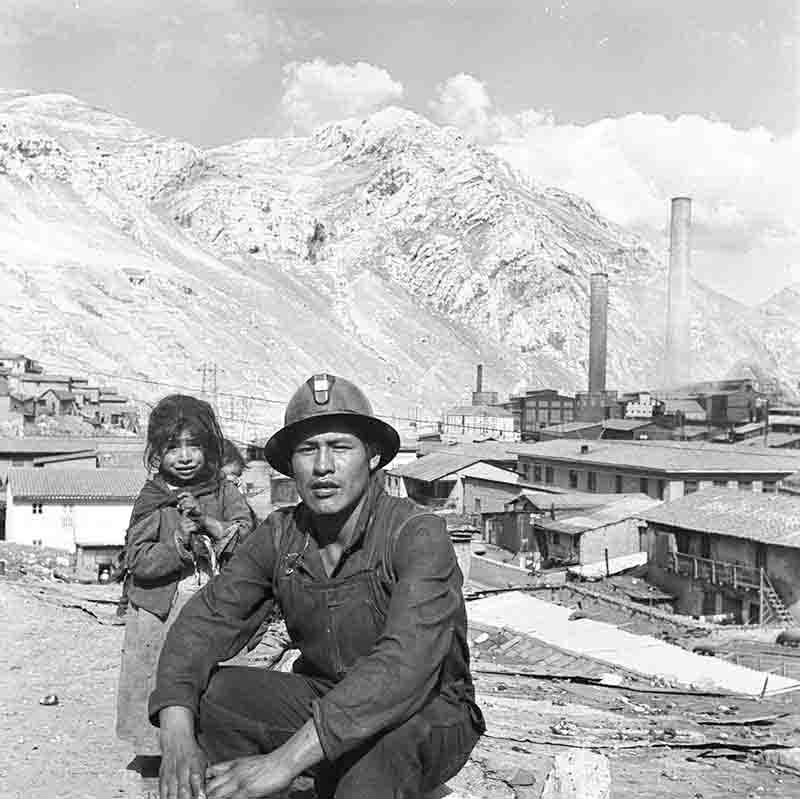

There was one question that was posed particularly insistently: What are the Russians like? Are they polite and friendly, charming or gruff, are they open-minded? After thinking about it for some time, I always only came up with one answer: that the human being is shaped by the surroundings in which he lives.

And that is particularly true of Russia. For me, the shot of the crowd at the All Union Agricultural Exhibition in Moscow is, as strange as it may sound, a landscape photograph.

Just look at the faces. That is Russia the way we imagine it: soldiers, farmers, cities. There's a lot of Khrushchev in those people.

Insight into the life of a photo reporter

You don't need special cameras or highly expensive photographic equipment for landscape photography. What counts is the perception, the eye. Nor do you have to travel half way around the world to take landscape photos.

A street you see every day of your life and that never seemed to be of any particular interest can suddenly become a fascinating motif if you really look at it closely.

Just as tastes have changed in the art of painting over the decades, they have also changed in photography, and especially in landscape photography.

I always try to capture something extra in the landscape, because as I said, the photo journalist’s landscape is not willows by the river or beeches in the fog, it is much more a disturbed landscape.

Just as the landscape forms the people, and I could cite numerous examples of this, people also put their mark on the landscape.

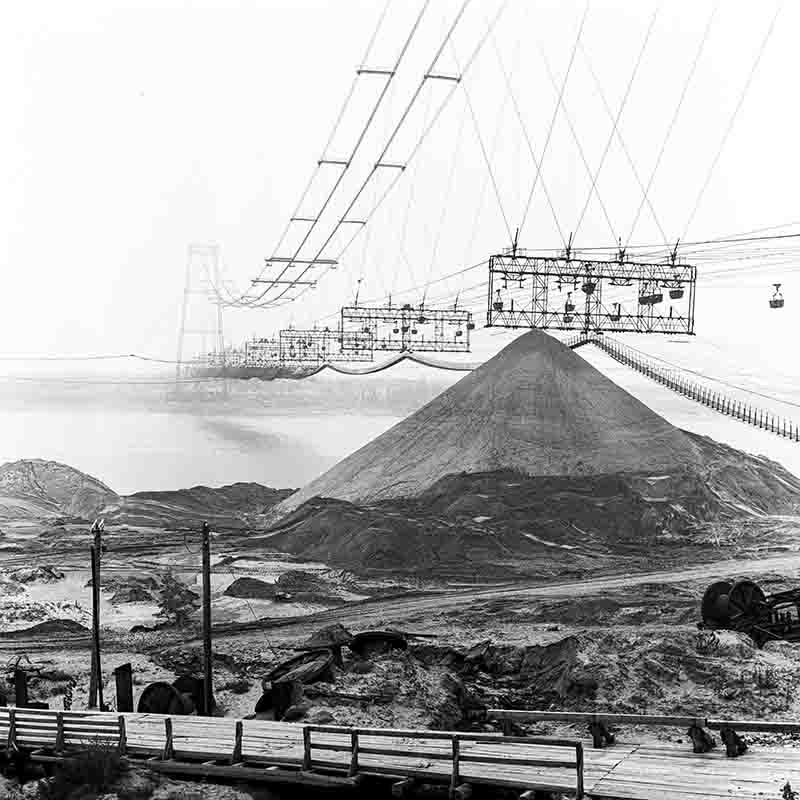

They erect trams and gondolas in the most untouched mountain ranges, they drown entire districts in manmade reservoirs, they destroy the harmony of rolling hills with mines and pit frames, I could go on and on.

Disturbed Landscapes

For us, the engineered landscape has already become an accustomed sight. So we needn't go looking for a little piece of earth free of all traces of human activity, for it is the landscape altered by man that repeatedly gives us something new, that offers us fascinating motifs.

Of course there is still the lovely natural landscape. It is the same one we have known for centuries, but it has gained a sterile touch now. The photo journalist’s landscape has to be more than just a pretty picture; it has to make a statement.

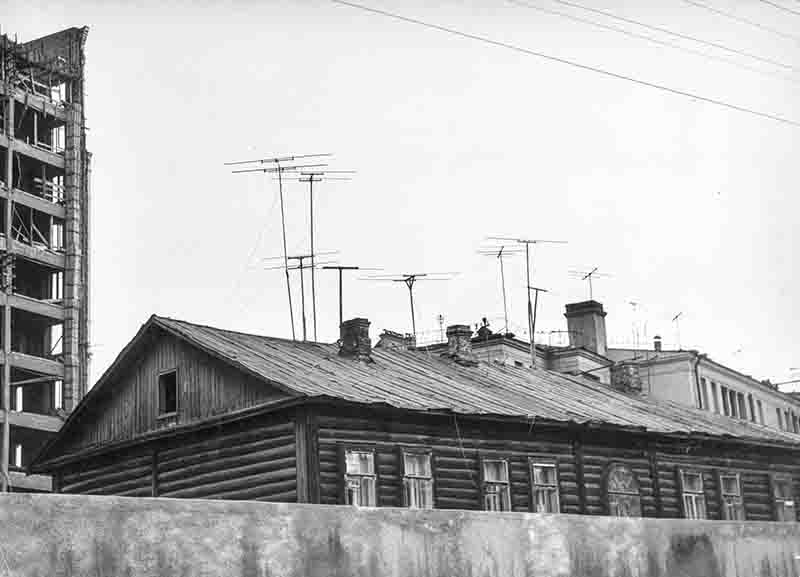

The subject of the photograph, be it in the foreground, centre or background, should be in focus. Take any city street, which can look very romantic and at the same time very realistic with its oil smears in the early morning sunlight.

A forest of television antennas can completely alter the impression of a sleepy small town. These images harbour no tendency to be cliched, as can so easily be the case with floral landscape photography.

Lessons from Peter Bock-Schroeder

My personal opinion is: Who "sees" well will also be able to take an appealing landscape photo.

That is to say a photo that is not melodramatic but realistic, not cute and playful but uncontrived and honest. The landscape deserves to be photographed the way it presents itself to us.