The view from the study of French engineer and inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in 1826 is regarded as the world's first and earliest existing photograph. He was the first to demonstrate a successful photographic process. Every photo that has ever been taken, and every photo that will be taken in the future, goes back to that first moment.

Niépce's view from the study

It becomes clear that the history of the birth of photography, cinema and television as a collective can be attributed to a single point in time. More precisely, to the year 1826.

The first photographer ever

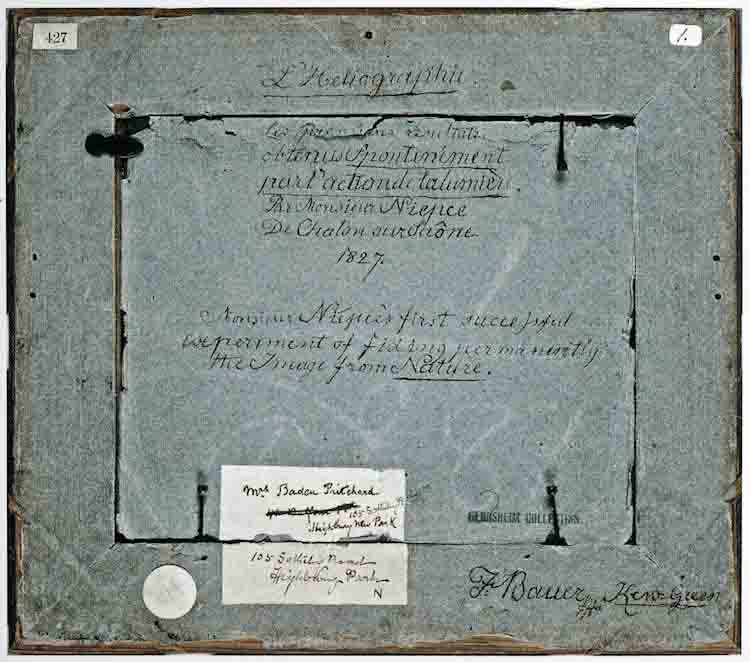

Monsieur Niépce' first successful experiment in permanently fixing an image from nature, noted on the back of the "view from the window".

The story of Joseph Nicéphore Niépce

The view from the study of French engineer and inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in 1826 is regarded as the world's first and earliest existing photograph.

Scientific data-based findings shed new light on the early history of photography, compared to what has been described in published literature.

Niépce’s work is remarkable in that he was the first photographer ever.

For he was the first person to take a photograph that was permanently fixed in such a way that it did not change when exposed to light.

Nicéphore Niépce was able to carry out the entire process from the light-sensitive plate to the exposure in the camera, to the development and fixing of the image for posterity.

He was the first to demonstrate a successful photographic process. Every photo that has ever been taken, and every photo that will be taken in the future, goes back to that first moment.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce was born on March 7, 1765, into a wealthy family.

His father was a counsellor to the king, and his mother was the daughter of a prominent lawyer.

In his childhood, Niépce showed great interest in inventions, but initially prepared for a clerical career, which he ended in 1792 in favour of an officer's career.

At the beginning of the French Revolution in 1789, the 24-year-old left the army due to his monarchist convictions.

When Napoleon came to power, Niépce returned to the ranks of the military troops and took part in the campaigns in Sardinia and Italy.

From about 1787 he used the name Nicéphore Niépce. A name derived from the Greek, Victory-bringer, and a pun referring to his surname.

From 1795, he worked as a civil servant in the administration of the Nice district.

In 1801, the family returned to Chalon-sur-Saône, Joseph Niépce's hometown.

Together with his brother Claude, he devoted the rest of his life to scientific research and invention.

Their most successful innovation was the Pyréolophore, an internal combustion engine, the prototype of which they successfully used to power a model boat.

For several years up to 1813, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce worked on optimising the quality of lithography. His first photographic efforts were initiated in 1816.

He succeeded in briefly capturing images on chlorine silver paper with a camera obscura, though he was not yet able to fix them.

An exact date has not been recorded, but it is known from correspondence with his sister that from 1816 he was intensively researching printing techniques for the production of copies of works of art.

The first photographic experiments looked excellent at first but faded to black over time.

With his process, which he termed heliography, Niépce managed to copy a lithographic image directly onto a bitumen sheet in 1822.

After applying this solution to a glass plate, which he had covered with a copper- and tin-based alloy he then exposed for several hours in a camera obscura.

As the image hardened on the surface and became visible to the naked eye, Nicéphore Niépce treated the plate with lavender oil.

For the first time in history, he succeeded in permanently creating a precise visual representation.

Namely, a heliograph depicting Pope Pius being drawn by light.

However, this picture was destroyed when he tried to make more copies of it.

Fortunately, one of the prints he made remained intact.

After extensive experimentation, Nicéphore Niépce took what experts call the world's first photograph.

The view from the window of his study on the Le Gras estate in Saint-Lou-de-Warenn in the early autumn of 1826.

He exposed for eight hours, on a tin plate, made light sensitive with asphalt.

This direct positive is the world's first surviving light-sensitive photograph.

I am at the dawn of a new world, he then wrote. Nothing shows better the step than this first image, today blurred, but which for the very first time is painted spontaneously by nature.

In 1827, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce became acquainted with Loui Daguerre, the wealthy owner of the Paris diorama, who offered him his collaboration.

He was concerned that developing his photographic process further would overwhelm his family finances.

In 1829 Niépce partnered with Daguerre, who was one of the few people interested in his innovation.

He hoped to draw capital for his invention from Louis Daguerre's connections and skills as a showman.

At the age of 64, Nicéphore Niépce signed a ten-year contract with Loui Daguerre to further develop his method of creating images of nature.

The contract contained a clause according to which his son Isidore was to become the heir in the event of his father's death before the contract expired.

Niépce exchanged letters with Louis Daguerre about the commercial potential of the invention and new chemical processes.

Furthermore, he sent a detailed description of his heliographic process and explained his technical approach.

Daguerre visited Le Gras in 1829 with great enthusiasm and was taught the techniques from Niépce.

Later that year, Niépce visits his sick brother who resided close to London.

During this visit, he became acquainted with the British botanist Francis Bower, who was a member of the Royal Society.

Bower was fascinated by the heliographic experiments and suggested a comprehensive scientific report to the prestigious Royal Society.

With great enthusiasm, Nicéphore Niépce prepared his presentation and composed all the necessary documents.

To his great disappointment, however, the Royal Society showed no interest; the reason was probably that Neeaybs, fearing rivals, had not given precise details of the steps involved, so that the Academy rejected his application for this reason.

Completely discouraged, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce departed.

He entrusted his work samples and notes to Bower, who, aware of their importance, carefully preserved them. Monsieur Niépce' first successful experiment in permanently fixing an image from nature he noted on the back of the "view from the window".

On July 5th 1833, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce suffered a stroke and died, aged 68, at the La Grass estate in Saint-Lou-de-Warenn, leaving his family virtually penniless.

His photographic process remained unfinished, and all his research and inquiries into photochemistry remained in the hands of Daguerre, who had contributed with only a minor contribution to the shared project.

Loui Daguerre continued to work on adjusting the heliographic method with his process.

Aptly called the Daguerreotype process for more than a century, Daguerre was credited as the maker of the earliest surviving photograph.

The Neeaybs heliograph passed through a chain of private hands in Britain in the 19th and 20th centuries before it was purchased by the Harry Ransom Centre in 1963.

More than 100 years after those eight hours at the window, the long misunderstood genius Joseph Nicéphore Niépcereceived the fame he deserved.

Today the oldest surviving photograph is part of the Gernsheim Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.