Bolivia has had more than 500 years of nonstop mining. It is estimated that only 10 per cent of the country's mineral resources have been extracted to date. The most economically important metals and industrial minerals include zinc, lead, tin, gold, silver, copper, tungsten, sulfur, potassium, borax, and semi-precious stones.

Mining in Bolivia began in 1545 when Cerro Rico was discovered, a mountain of silver ore. An economic system started to develop, deposits were exploited and the city of Potosí was born, growing out of the soil with the arrival of the first miners.

The Cerro Rico de Potosí was the richest source of silver in the history of mankind. 80% of all the world's silver came out of this mine, which increased the wealth of the entire planet. This wealth produced the construction of new cities and empires and served to finance some of the wonders of the world.

Having defeated the military and toppled the Ballivián government, Siles served as provisional president from 11 April 1952 until 16 April 1952, when Estenssoro returned from exile. The 1951 electoral results were upheld, and Paz Estenssoro became constitutional president of Bolivia with Siles as his vice-president.

During the MNR's first 4 years in the office, the government instituted far-reaching reforms, including the establishment of the universal vote, nationalization of the largest mining concerns in the country, and the adoption of a major agrarian reform.

In 1956 Estenssoro left the office, as the Bolivian Constitution forbade a sitting president from running for another consecutive term. Siles, his logical successor, easily won the elections of 1956 and became President of the Republic on August 6, 1956.

For three centuries Bolivia was the world's largest producer of silver. In 1976 the United States Geological Survey, the Bolivian Geological Survey (Servicio Geológico de Bolivia), and others discovered large reserves of lithium in 1976.

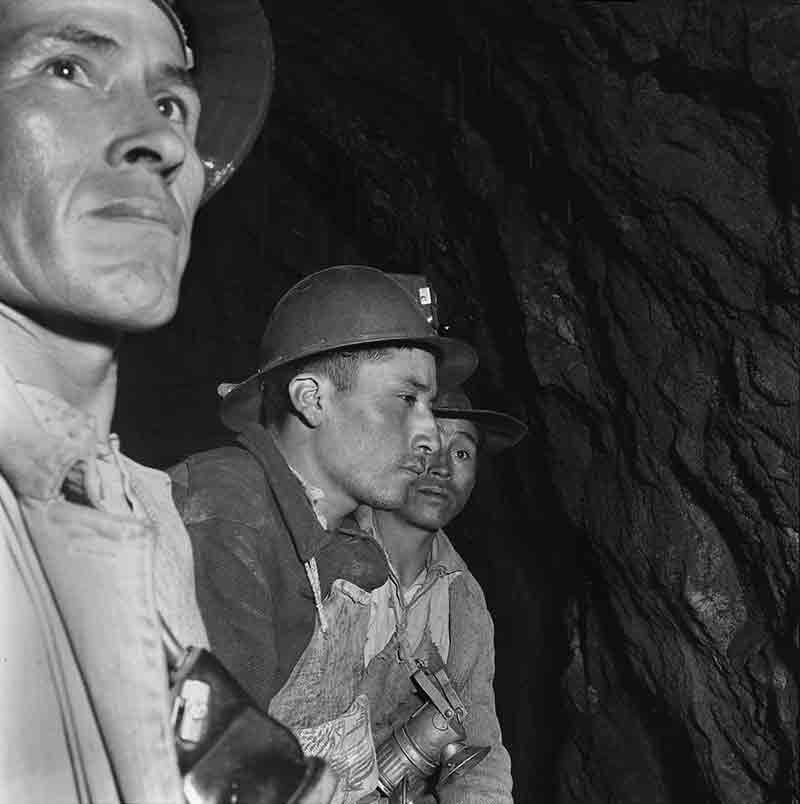

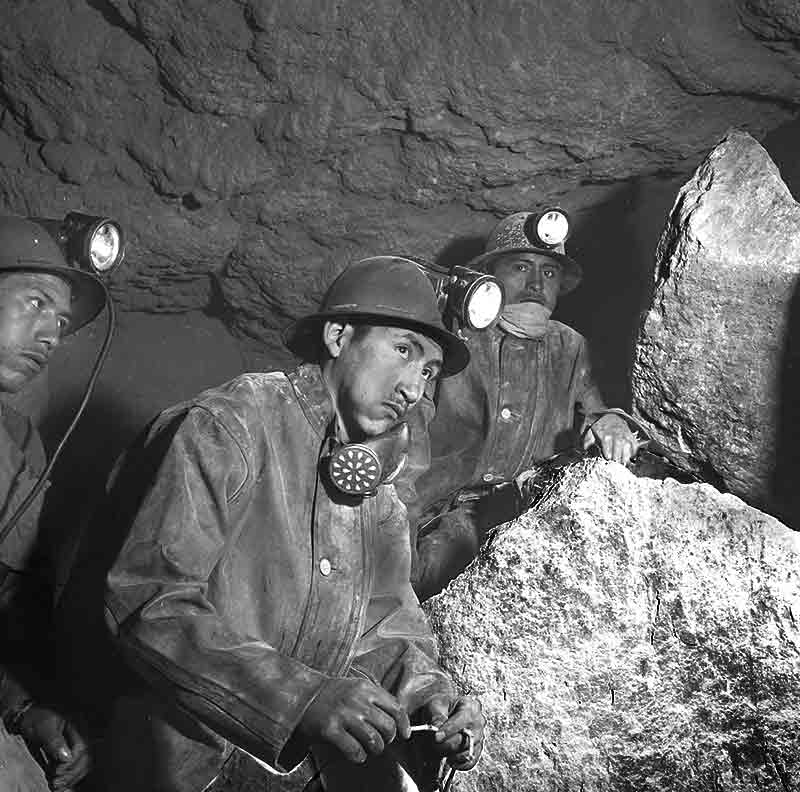

Coca leaves, which react with saliva and calcium carbonate to produce a strong, pain and hunger killing stimulant, are necessary for the duration of work shifts, which sometimes last 72 hours. Men are squeezed into tiny spaces and spend hours pounding a 20-inch hole out of the rock with only a metal bar and a hammer.

They then insert a stick of dynamite, blow out a piece of rock, and have their assistants -- young boys, many of them not yet in their teens -- carry the debris out of the mine in a wheelbarrow.

The ritual to honour El Tio, the devil guardian of the cave. The miners give him offerings of alcohol and cigarettes and pause to chew coca leaves. The coca is a narcotic that numbs the senses and staves off hunger and exhaustion.

Inside the mine, El Tio is like a god. The miners all believe in him. They are paying tribute to him and asking for more protection, more production, and no accidents.

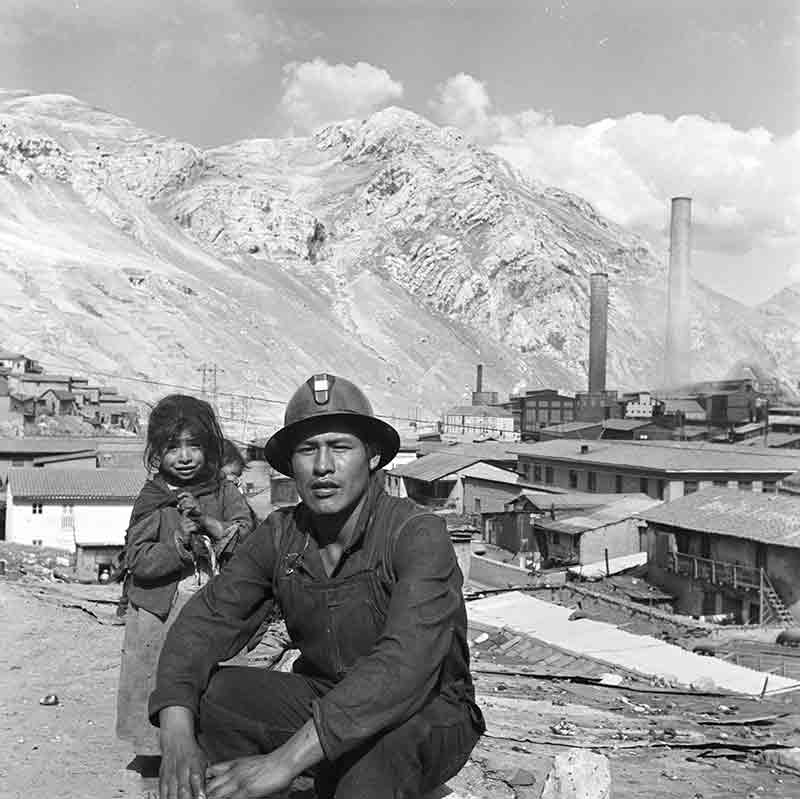

The extreme temperatures and poor ventilation exact a heavy toll. Silicosis or black lung disease is caused by years of breathing dust-filled air. It will end a man's life in 10 years.

The hospital in Potosi is filled with miners whose only lifeline is a tube attached to an oxygen tank. Cerro Rico de Potosí is known as the "mountain that eats men" because of the large number of workers who died in the mines.

Mining in Bolivia has been a dominant feature of the Bolivian economy as well as Bolivian politics since 1557. Colonial era silver mining in Bolivia, particularly in Potosí, played a critical role in the Spanish Empire and the global economy.

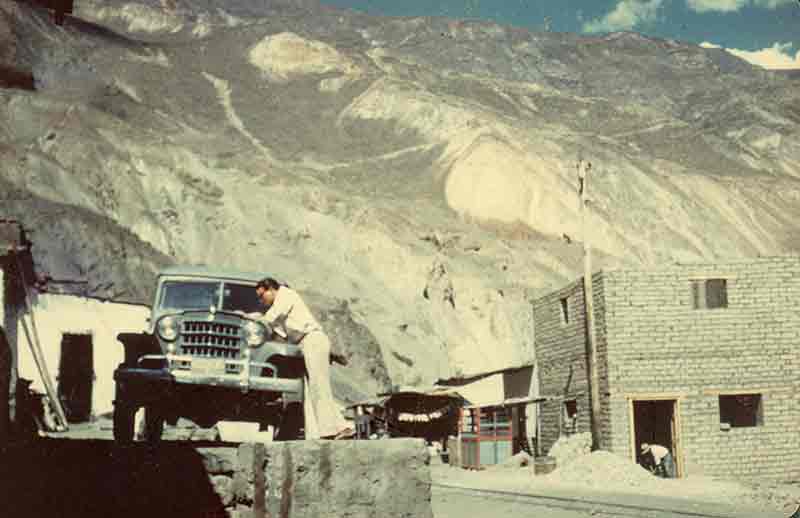

The average miner lived in a hut; no bed, no windows, 5 or more family members cramped together. Even as late as 1961, the average lifespan was 25 and infant mortality was at 60%.

The 20th century gave rise to to a new kind of photographer; both social reformer and globe-trotting photojournalist who hunted news stories for the great tabloid empires. Photography had entered an era of unparalleled creativity, propelled in part by sophisticated new picture magazines.